Preliminary Draft

Comments will be appreciated

Revision 4-9-24

1. Introduction

Computer scientist Professor Geoffrey Hinton[1] told BBC Newsnight [2] that the government should establish a universal basic income to address the impact of artificial intelligence (AI) on ordinary jobs. He explained that while AI would increase productivity and wealth, the financial benefits would accrue to the rich, not to those whose jobs would be lost, which would be detrimental to society.

Traditional Computing relies on explicit instructions with specific rules and logic (software), and the computer follows those rules step by step.

Deep Learning Neural Computing works differently. Instead of following explicit instructions through access to databases, it learns patterns and makes inferences based on those patterns. The ability to learn, adapt, and improve over time is a key characteristic that differentiates intelligent machines from traditional machines or software.[3]

Professor Hinton’s foresight assumes a high degree of substitutability of human work with work done by AI. What distinguishes this from past trends?

From complementarity to substitutability

Since the Industrial Revolution, human labor has typically been complemented by machines: capital and labor have generally been in a complementary relationship. The more efficient the machines, the higher the labor productivity and, consequently, wages. [4]

In the early days of the Industrial Revolution, economists have recognized that dramatic consequences for wages and population can result from the introduction of machines (Ricardo, 1821). And indeed, at the start of the Industrial Revolution, machines destroyed more handcrafted jobs than industrial jobs they created. Yet since then, the capital stock of machines and technical progress have raised, increasing demand for labor. If anything, computers have intensified this trend – until now.

With the recent development of artificial intelligence based on deep learning neural networks, the issue of substitutability becomes as much an analytical concern as it is a social and political one. AI makes the headlines and the political agenda.

The threat of AI-induced massive unemployment, as predicted by some, is not the only concern. Regardless of the similarity to human labor, AI labor is still a machine i.e. a capital good and under specific supply structures, the “capitalist” reaps all the benefits with no longer a market driven need to share a part of its revenue with labor. This leads to an unequal society.

We do not need science fiction or some prospective analysis to understand the implications. History and economic theory will guide us, albeit in a highly stylized way. Historians might be unsatisfied and possibly shocked; economists, used to stylized facts, will feel more at ease.

2. History

From an institutional point of view, a slave belongs to the owner (he is a possession) and is like a capital good (instrument of action).

The substitutability of human labor and AI labor is not so different from that between human labor and slavery. The slave is own by his “master”, as defined by Aristotle:

Aristotle (350 BCE) – “The master is only the master of the slave; he does not belong to him, whereas the slave is not only the slave of his master but wholly belongs to him. Hence, we see what the nature and office of a slave is; he who is by nature not his own but another’s man, is by nature a slave; and he may be said to be another’s man who, being a human being, is also a possession. And a possession may be defined as an instrument of action” Politics, Book 1, Part IV.

Rome’s imperial expansion dramatically increased the inflow of slaves, and farming was increasingly done on large estates using slaves. Free peasants could no longer compete. According to Keith Hopkins [5], between 80 and 8 BC, in two generations, roughly half the free adult males in Italy left their farms [6]. Many went to Rome, forming a proletariat of free landless citizens, depending on handouts of free food supply.

The political solution was “Panem et Circenses”.[7]

In the pre-industrial age, only an increase in the endowment of labor could increase the total output of the economy, hence the role of conquests and war captives becoming slaves. [8]

With the Industrial Revolution, the production of goods can be modeled by a production function that has capital (capital goods or machines) rather than land as the main production factor associated with labor. Through capital deepening (investment) and technical progress, the output per hour worked (labor productivity), increased over time paving the way to higher wages.

The intertwining of the industrial and liberal revolutions is not a coincidence. While landowners needed a permanent and stationary workforce, manufacturers needed to freely hire and fire the labor force according to changing market conditions. The dawn of the Industrial Age is associated with the hideous army of proletarians, but it is also the dawn of civil liberties and education for the masses [9]. The capitalists who needed a skilled and educated workforce had an interest in policies promoting mass education, whereas landowners, who sought to limit the mobility of the rural labor force, favored policies that deprived the masses of education.

The emergence of a free labor market is the “Great Transformation” [10] brought about by the Industrial Revolution, which allowed for greater geographical and social mobility. “The real change brought about by the 18th century “is not the necessity to work, but the freedom to work” . [11]

3. Economic Theory

The United Nations System of National Accounts (SNA) implemented after WWII, along with Robert Solow’s [12] seminal paper (1956) provided the foundation of economic growth theory and growth accounting analysis. Improvements in the SNA system and collaborative research sponsored by the U.N., the OECD and the European Commission have delivered huge and highly detailed databases based on national accounts.[13]

The purpose of this kind of approach is to measure the contribution of labor (L), capital (K), and the state of technology (A) to economic growth (g), as measured by the gross domestic product (GDP).

Y= f (A, K, L)

The growth rate (g) equals the growth rate of total factor productivity (technological progress) A plus the weighted average of the growth rates of the two inputs K and L.

A second relationship relates the evolution of the knowledge stock to investments in R&D, locally available knowledge and spillovers from the stock of “global knowledge”. [14]

In a Solow-type model, the convergence of wages to labor productivity is “the name of the game” (Alan Blinder). It perfectly captures the “Great Transformation of the Industrial Revolution” in so far that technical progress (A) and capital deepening (K/L) increased labor productivity and, hence wages.[15]

If productivity is the name of the game, structural adjustment is the price to pay, and it is the demand side that drives structural changes. Productivity gains in a sector where demand is stagnant, even when prices are lowering (inelasticity), will reduce employment and vice-versa. Price inelasticity explains why farm mechanization in advanced economies eventually destroyed more jobs than slaves did during the Roman Empire.

Can we keep the Solow and growth accounting models unchanged when considering intelligent machines?

The growth accounting contribution of computers and information technologies (ICT) to economic growth, productivity, and employment received wide attention in the ’90s and beyond, particularly by the OECD/EC EUKLEMS research consortia.

They made a distinction between ICT capital goods and non-ICT capital goods, while leaving the basic Solow model unchanged, especially the complementarity between labor and capital of any type.

The main reason behind a higher contribution to economic growth of ICT capital was their falling prices increasing their relative contribution to economic growth. Saying with greater precision, much of technological progress is embodied in capital and their diffusion through the reduction in their price, in this case semiconductors.

When referring to intelligent machines, a new and very specific ICT capital good is introduced in the analysis. Indeed, while for decades artificial intelligence research based on conventional software and hardware delivered rather disappointing results, the release of Open AI Chat GPT [16] in November 2022 symbolized the start of a social and media hype about AI. Even non-experts have come to understand the meaning and power of artificial intelligence based on deep learning (neural networks) for the software part and on graphic power units (GPU) for the hardware.[17]

The radical change introduced by AI is the machine learning process through data acquisition, training, validation, and deployment. From a non-technical point of view, the fundamental trait is access to a critical mass of data without which there is no deep learning.

At first view, at macro level, in a Solow model, L and K must be changed.

a. Total labor (L) would have two components, human labor (LH) and intelligent machines (LAI).

Y = f( A, (LLH + LAI ) , K

Strictly speaking, an increase in total labor is a source of economic growth. When human labor and intelligent machines become increasingly substitutes, or in other words, when labor productivity decreases relative to intelligent machines productivity, the economy will keep growing only if sectoral changes are providing enough jobs to compensate the displaced ones. Considering a longer term and a more dynamic analysis, things can go awry. When considering different sectors, the wage rate is determined by the marginal productivity of labor of each sector, meaning that sector labor displacements to low skill / low productivity jobs can be harmful. On top of that, there is a Malthusian issue; the supply of intelligent machines, as for any kind of capital good, can increase as fast as requested by market conditions, while total population is rather stagnant or declining. [18]

b. Separate among capital goods (K) those that are specifically underpinning AI (KAI)

The purpose of distinguishing capital goods (K) that specifically underpin AI (KAI) is to measure capital deepening in KAI . As already mentioned, much of technological progress is embodied in capital and their diffusion through the reduction in their price (computers/semiconductors).

EUKLEMS growth accounting has shown that the contribution of ICT capital to economic growth since the ’90 was mainly driven by technical progress in semiconductors (Intel type CPU chips). In the AI case, the focus would shift to graphic chips, particularly Nvidia-type GPU chips. While Intel was the dominant supplier in the CPU market, Nvidia currently dominates the GPU market, where demand far exceeds Nvidia’s production capacity. As a result, antitrust authorities are concerned about Nvidia’s power to control the allocation of this scarce but essential technology. Several companies, including AMD, Intel, Apple, Google, Amazon, Alibaba, Huawei, and Tesla, are developing AI GPUs to challenge Nvidia’s market dominance. This R&D-driven competition will speed up the diffusion of intelligent machines.

c. Make a distinction between AI internal and external platforms

The market is increasingly supplying both consumer and producer goods with embedded AI, ranging from AI image processing in cameras and mobile phones to AI-controlled medical equipment. With embedded AI, the buyer retains the benefits of usage, and the consumer is willing to pay for the associated utility. Thus, microeconomic foundations are satisfied, and AI could be seen as a form of technical progress embedded in consumer and capital goods. However, this is not the full story

The concept of “embedded and disembodied” need a more detailed analysis. Essentially, this distinction revolves around the ownership and access to massive databases, which are crucial for training intelligent machines. Let us take a simple example. Hospital have often the legal obligations at country level to share their data, allowing these institutions to develop deep learning artificial intelligence using their common proprietary database. These hospitals own and use a specific internal platform. Provided they possess adequate computing resources, they own the results and the benefits of AI. In this scenario, this would be like expenses in R&D, which is captured by the standard growth accounting approach.

In the case of general-purpose external platforms, the user gains access to a platform and related service without ownership or control over it.

The business model behind the generative AI boom largely relies on the free, unauthorized use of various works from across the internet to train sophisticated software capable of producing human-like outputs. These works include art, music, videos, news articles, and social media posts. As lawsuits progress, a key question will be whether the use of such material to train AI models constitutes “fair use” or illegal infringement.”[19]

Companies like OpenAI and the GAFAM (Google, Apple, Meta, Amazon, and Microsoft) share a common strategy:

– Leveraging the Internet and its vast data resources to their advantage[20]

The big improvement in AI tech showcased by ChatGPT that kicked off the boom came from OpenAI feeding trillions of sentences from the open internet into an AI algorithm. Subsequent AIs from Google, OpenAI and Anthropic have added even more data from the web, increasing capabilities further.

The distinction between internal and external platforms is critical from a legal point of view.[21] Indeed, when the information comes from the user himself or the organization he belongs to, and is not public, it benefits from data protection, privacy and security legislations.

– Channeling large amounts of investment into computing power

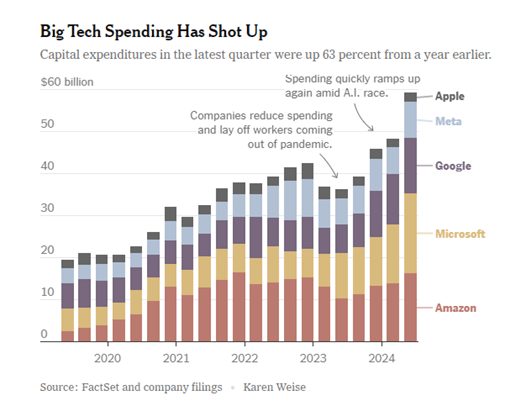

OpenAI released ChatGPT in November 2022, kicking off a race in Silicon Valley to build new AI products and get people to use them. “In quarterly earnings calls this week, Google, Microsoft and Meta all underlined just how big their investments in AI are. Meta raised its predictions for how much it will spend this year by up to $10 billion. Google plans to spend around $12 billion or more each quarter this year on capital expenditures, much of which will be for new data centers, Chief Financial Officer Ruth Porat said. Microsoft spent $14 billion in the most recent quarter and expects that to keep increasing “materially,” Chief Financial Officer Amy Hood said (…) Much of the money is going to new data centers, which are predicted to place huge demands on the U.S. power grid.”[22]

As published by the New York Times, August2, 2024

Tech Bosses Preach Patience as They Spend and Spend on A.I.

The benefits of AI for end users – whether consumers or enterprises- can be quick and substantial depending on the access price, which is typically kept low to attract a maximum number of subscribers. Consider services like translation, simultaneous interpretation, or movie dubbing where jobs are increasingly at risk due to the affordability and capabilities of AI platforms.

4. Tentative Conclusions

Drawing a comparison between intelligent machines and slaves is a necessary analogy to capture the unique feature of being at the same time labor and capital and Professor Geoffrey Hinton’s foresight on wages and inequality can be described by economic theory (3a and ref. 18).

The significance of this two-faced technology has been recognized at the governmental level in the U.S., Europe, Japan and elsewhere (3c and ref. 19). The availability of highly qualified software engineers (benefiting from knowledge spillovers in tech hubs like Silicon Valley) and the enormous costs associated with general-purpose AI platforms (in terms of computer power and energy consumption) has led to the dominance of a few companies (Ref.22). Notably, these platforms are currently concentrated in the U.S. and China. It is worth to notice that Chinese authorities favor non-proprietary open-source AI platforms.

The Chinese AI policy has two pillars:

- Be politically correct: compliance with Beijing’s strict censorship regime, which extends to generative A.I. technologies

- To foster the deployment of AI, China favors and supports an open-source strategy. “By making their most advanced A.I. technologies freely available, China’s tech giants are demonstrating their willingness to contribute to the country’s overall technological advancement as Beijing has established that the power and profit of the tech industry should be channeled toward the goal of self-sufficiency”[23]

Leaving aside the issue of proprietary and non-proprietary general purpose AI platforms, what conclusions can we draw about the economic consequences of AI.

The impact largely hinges on the elasticity of substitution between technology and labor, at macro, sectoral, and firm levels. Studies on Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) and robotics suggest that this elasticity is highly heterogeneous, particularly across different occupations. For instance, will AI boost the productivity of low-skill workers by complementing their abilities, as suggested by Brynjolfsson et al. [24] while threatening mid-range jobs like computer programming where AI may perform faster and more efficiently?

It is all depending on the sector and the skills you are referring to.

What will be or could be the outcome at macro-level? AI is of course at a too early stage of deployment to expect a clear answer. The actual rush on AI, as often reported by the press, is mostly driven by a “let’s see how it works” approach, at a low cost of experimentation and no firm decisions yet on their business model and employment.

As for the impact of ICT and robots, the main concern should be about wage polarization. Will the AI shock hit the middle of the wage distribution more severely than at the bottom and top distribution? Although there is a genuine risk that our society evolves into a highly sophisticated one, yet with a growing class of impoverished individuals, the impact of AI on inequality remains ambiguous.[32]

Ave Imperator, morituri te salutant

Background notes

European Commission AI Act [25]

AI Act enters into force: On 1 August, the EU AI Act took effect, aiming to promote responsible AI development and deployment in the EU. Initially proposed in April 2021 and agreed upon by the European Parliament and the Council in December 2023, the Act addresses potential risks to citizens’ health, safety, and fundamental rights. It sets clear requirements for AI developers and deployers while minimizing administrative and financial burdens on businesses. The Act introduces a uniform framework across EU countries, employing a risk-based approach:

1) Minimal risk: systems like spam filters face no obligations but may voluntarily adopt codes of conduct.

2) Specific transparency risk: systems like chatbots must inform users they are interacting with machines, and AI-generated content must be labelled.

3) High risk: for instance, systems in medicine and recruitment must meet stringent requirements, including risk mitigation and human oversight among others.

4) Unacceptable risk: for example, systems enabling “social scoring” are banned due to fundamental rights threats.

European Commission general-purpose AI (GPAI) Code of Practice [26]

The European Commission AI Office has issued a call for expression of interest to help draft the first general-purpose AI (GPAI) Code of Practice. Eligible participants include AI model providers, downstream providers and other industry organizations, civil society, rightsholders, academia and other independent experts.

Google, Amazon, Meta, Apple and Microsoft are under a magnifying glass from agencies like the Federal Trade

While big tech companies typically buy start-ups outright, they have turned to a more complicated deal structure for young A.I. companies. It involves licensing the technology and hiring the top employees — effectively swallowing the start-up and its main assets — without becoming the owner of the firm. These transactions are being driven by the big tech companies’ desire to sidestep regulatory scrutiny while trying to get ahead in A.I., said three people who have been involved in such agreements. Google, Amazon, Meta, Apple and Microsoft are under a magnifying glass from agencies like the Federal Trade Commission over whether they are squashing competition, including by buying start-ups. Regulators are watching. The F.T.C. is working on a broad study of A.I. deals between start-ups and Microsoft, Amazon and Google, the agency said in January. It is also investigating whether Microsoft should have notified regulators about the Inflection deal, which would have subjected the arrangement to more immediate scrutiny, a person with knowledge of the matter said. Since the A.I. boom took off in late 2022, it has transformed tech deals. Investors initially raced to pour money into A.I. start-ups at high valuations. That led to an unusually frenzied pace, with start-ups such as Anthropic raising large sums frequently and agreeing to various funding conditions, such as using chips and cloud computing services from the companies that invested in them. That excitement cooled as it became clear that some high-profile A.I. start-ups would not succeed, creating an opportunity for big tech companies to swoop in with nontraditional deals.[27]

The Justice Department and states had sued Google, accusing it of illegally cementing its dominance

Judge Amit P. Mehta of U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia said in a 277-page ruling that Google had abused a monopoly over the search business. The Justice Department and states had sued Google, accusing it of illegally cementing its dominance, in part, by paying other companies, like Apple and Samsung, billions of dollars a year to have Google automatically handle search queries on their smartphones and web browsers. The government argued that by paying billions of dollars to be the automatic search engine on consumer devices, Google had denied its competitors the opportunity to build the scale required to compete with its search engine. Instead, Google collected more data about consumers that it used to make its search engine better and more dominant.[28]

Antitrust authorities are concerned about Nvidia’s power

Nvidia dominates sales of chips known as graphics processing units, or GPUs, which make it possible to create A.I. systems in data centers. Customers want more of those chips than Nvidia can produce. As a result, antitrust authorities are concerned about Nvidia’s power to determine how a scarce but essential technology is being allocated. That success has quickly brought government scrutiny. Authorities with the European Union, Britain and China asked the company for information about its sales of those important chips, allocation of supplies and investments in other companies, according to Nvidia’s financial filings.[29]

One example of AI

Google DeepMind’s pioneering AI weather forecasting technology, GraphCast, has won the 2024 MacRobert Award – the UK’s longest-running and most prestigious prize for UK engineering innovation. [30] Rémi Lam, GraphCast’s lead scientist, said his team had trained the A.I. program on four decades of global weather observations compiled by the European forecasting center. “It learns directly from historical data,” he said. In seconds, he added, GraphCast can produce a 10-day forecast that would take a supercomputer more than an hour. Dr. added, is now building on “the great work” of the experimentalists to create an operational A.I. system for the agency. (…) Impressed by such accomplishments, the European center recently embraced GraphCast as well as A.I. forecasting programs made by Nvidia, Huawei and Fudan University in China [31]

[1] Professor Hinton is a pioneer of neural networks, which form the theoretical basis of the current explosion in artificial intelligence. Until last year he worked at Google but left the tech giant so he could talk more freely about the dangers from unregulated AI.

[2] BBC Newsnight 18 May 2024

[3] Short definition based on ChatGPT. “Response to [specific question or topic].” OpenAI, 2024

[4] For the sake of simplicity, the (Solow) neoclassical model serves as the theoretical foundation for introducing the central issue at the beginning of this analysis. The text will indicate when it is no longer relevant.

[5] Keith Hopkins (2009), On the Political Economy of the Roman Empire (downloadable)

[6] The widespread use of slave labor in the Roman Empire had a significant impact on the job market and economic opportunities for free citizens. While it’s an oversimplification to say that slavery alone “destroyed” free citizens’ jobs, it certainly created economic challenges and shifts in several ways. Large estates (latifundia) owned by wealthy elites often used extensive slave labor, which allowed these estates to produce agricultural goods more cheaply than small, free citizen farmers could. This competition made it difficult for small farmers to compete, leading many to lose their land and livelihoods.

[7] To a fixed number of adult male free citizens

[8] Nevertheless, total population was constrained by the amount of food that the agricultural sector was able to supply. The pre-industrial model, also called the Malthusian model, “had a negative feedback loop whereby, in the absence of change in technology or in the availability of land, the size of the population was self-equilibrating

[9] Oded Galor, Omer Moav and Dietrich Vollrathe (2006), Land Inequality and the Emergence of Human Capital Promoting Institutions

[10] Karl Polanyi, 1944, The Great Transformation

[11] Robert Castels (1995), Les métamorphoses de la question sociale

[12] 1987 Nobel Prize for Economics

[13] To mention one, the EU KLEMS database (University of Groningen) originally financed by the European Commission provides data measuring economic growth (GDP), productivity, employment creation, capital formation and technological change at the industry level for all European Union member states from 1970 onwards.

[14] For a review of the different approaches, see Eric Bartelsman, 2010, Searching for the Sources of Productivity

[15] Please note that the Solow model is at macro level and need alternatives approaches for heterogeneous firms and productivity.

[16] Founded in 2015

[17] Nvdia has an estimate 90 percent share of the A.I. chip market. Reminds us of the similar share of Intel during the PC golden age.

[18] For a more detailed analysis, see Robin Hanson (1998), Economic Growth Given Machine Intelligence.

Author’s Note – To my knowledge, Robin Hanson’s paper is the first published article that applies a standard Solow-type model to the study of intelligent machines.

[19] Washington Post, August 14, 2024, AI’s legal reckoning is one step closer

[20] Lawsuits have been launched against OpenAI and other AI companies for using people’s work and data to train their AI without payment or permission. For example, The New York Times has sued OpenAI and its partner, Microsoft, about the use of the publication’s copyrighted works in A.I. development

[21] The distinction is not always straightforward. Is Co-pilot considered an internal platform when operating as an assistant, and an external platform when performing search-related tasks?

[22] The Washington Post April 25, 2024, Big Tech keeps spending billions on AI. There’s no end in sight

[23] New York Times, July 25, 2024, China is Closing the AI Gap With the United States

[24] Brynjolfsson, E, D Li and L Raymond (2023), “Generative AI at Work”

[25] The EU AI Act Newsletter, August 5, 2024

[26] European Commission, July 30, 2024, AI Act: Have Your Say on Trustworthy General-Purpose AI

[27] New York Times, August 8, 2024, The New A.I. Deal : Buy Everything but the Company

[28] New York Times, August 5, 2024, ‘Google Is a Monopolist,’ Judge Rules in Landmark Antitrust Case

[29] New York Times August 6, 2024, As Regulators Close In, Nvidia Scrambles for a Response

[30] Businessweekly.co 10 July 2024,

[31] New York Times, 29 July 2024, Artificial Intelligence Gives Weather Forecasters a New Edge

[32] Francesco Filippucci et al. 2024, Should AI stay or should AI go: The promises and perils of AI for productivity and growth, CEPR (downloadable and a highly recommended lecture)